As you may have already heard, my novella A Scout is Brave was nominated for a Shirley Jackson Award recognizing excellence in works of the psychological fantastic written by wryly cynical people with serious doubts about the decency of humanity.

Yeah, it’s a niche award, but it’s a niche made for me!

Last night in a ceremony gala at Readercon, a star-studded panel of presenters announced the winners, and alas, A Scout is Brave was not among them. Per the organization’s bylaws, I was frog-marched from the ballroom and stoned (with stones, not the other kind) in the town square.

As many of you know, I am doomed by my Scandinavian heritage toward dark contemplation, and I’m sure people close to me have been dreading my inevitable tailspin.

You know what, though? No tailspin.

As cliche as it sounds, the real award was being nominated in the first place: a sign of esteem from the jury of the award plus some extra recognition for the book. Many people approached me at Readercon to tell me they loved the story, including friends and mentors and even a few strangers.

When one of my favorite writers told me she had her fingers crossed for me, that was the win. When my MFA thesis advisor stood around with me after the ceremony commiserating, that was the win. When the award coordinator handed me my nominee’s rock, that was the win.

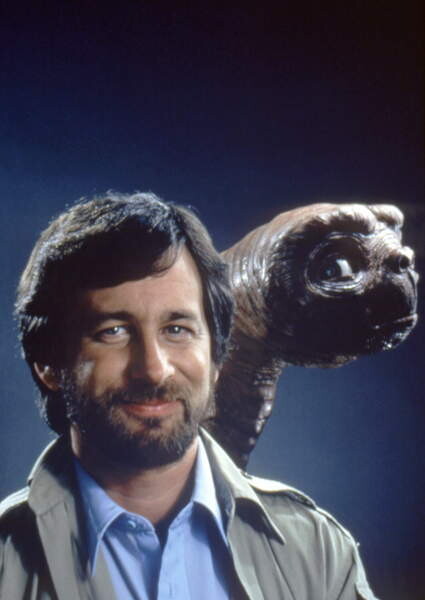

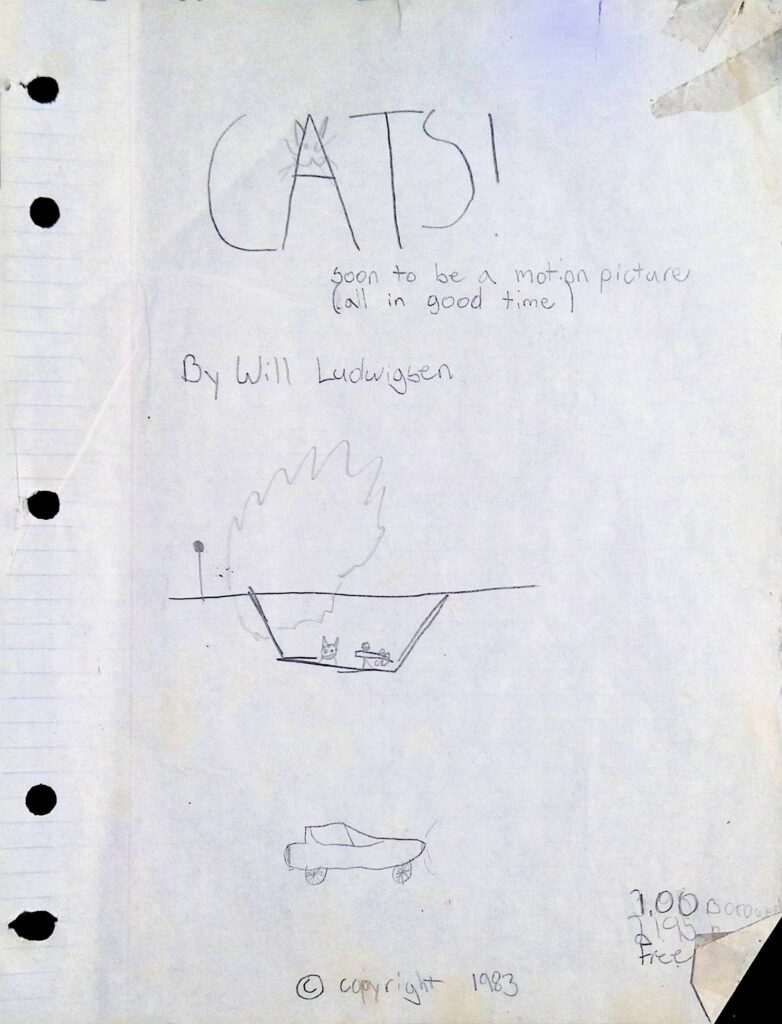

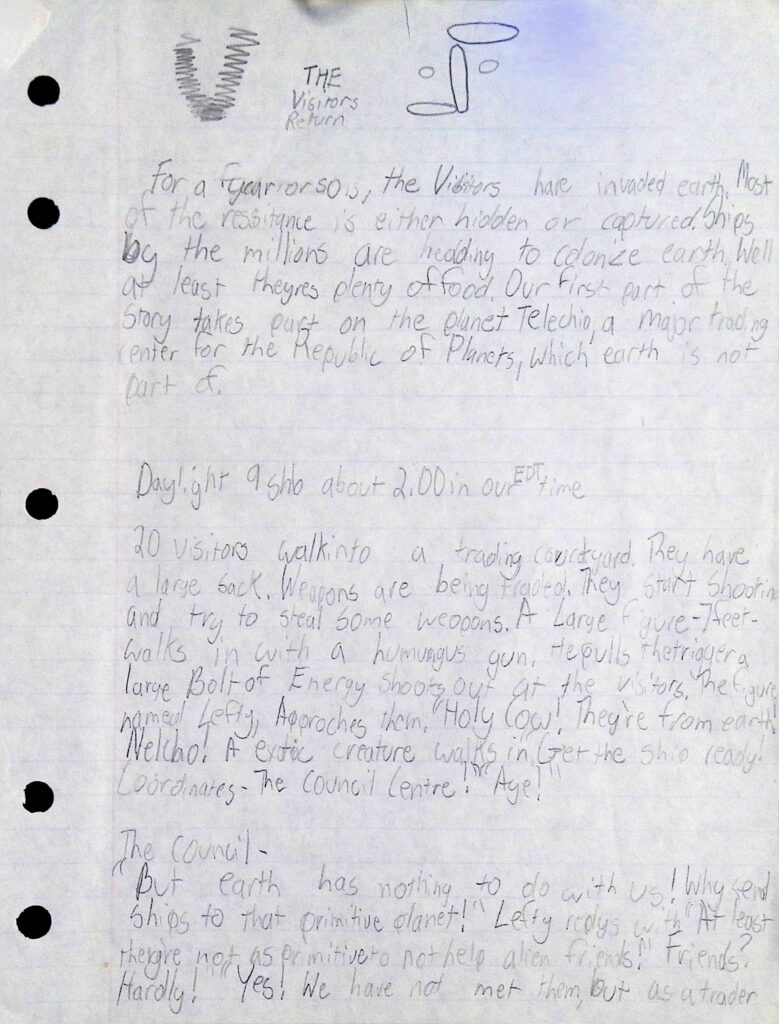

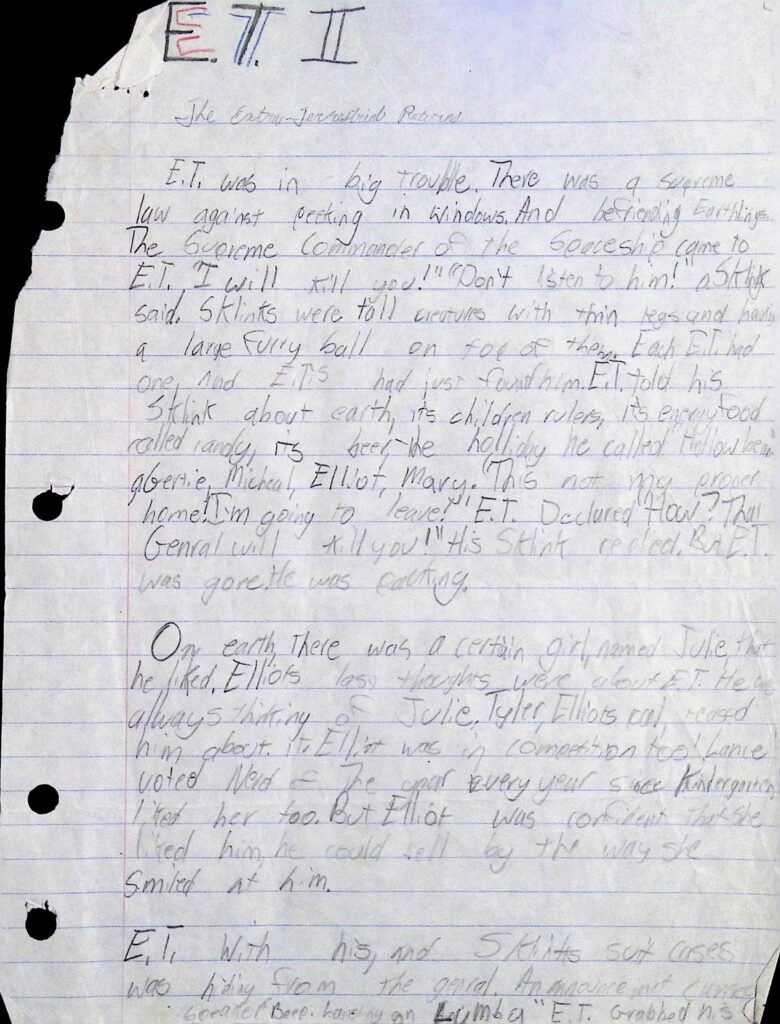

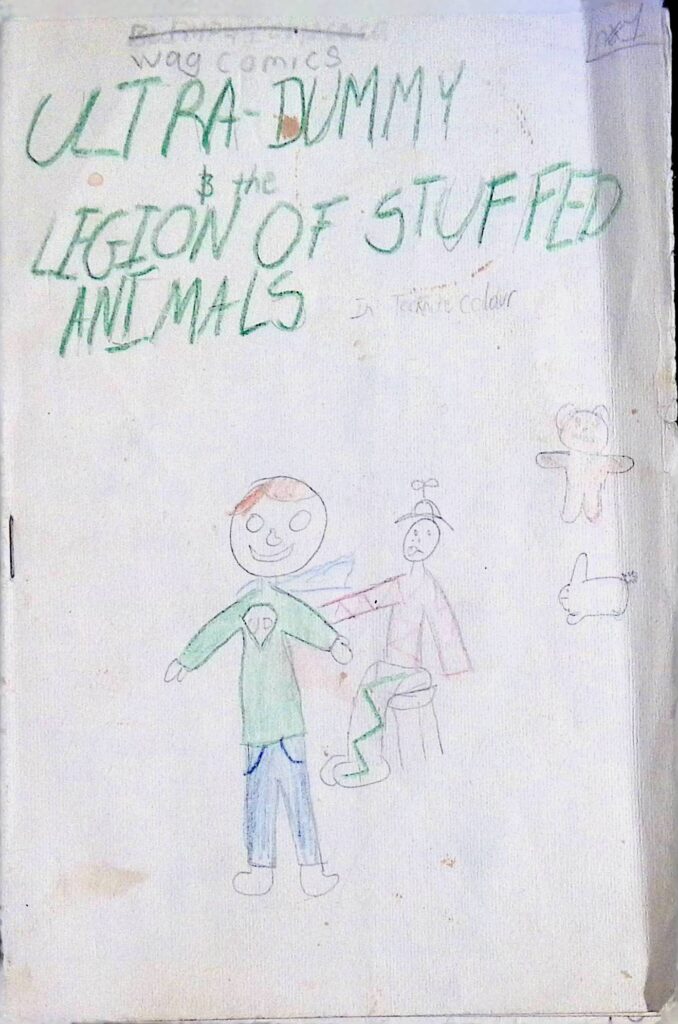

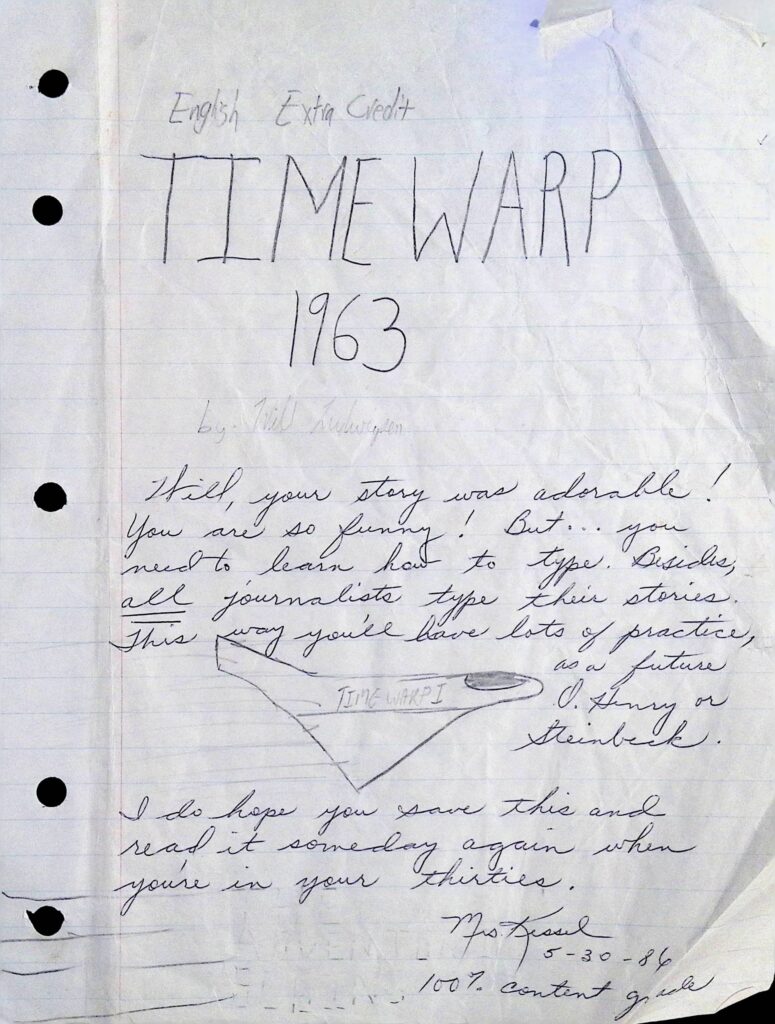

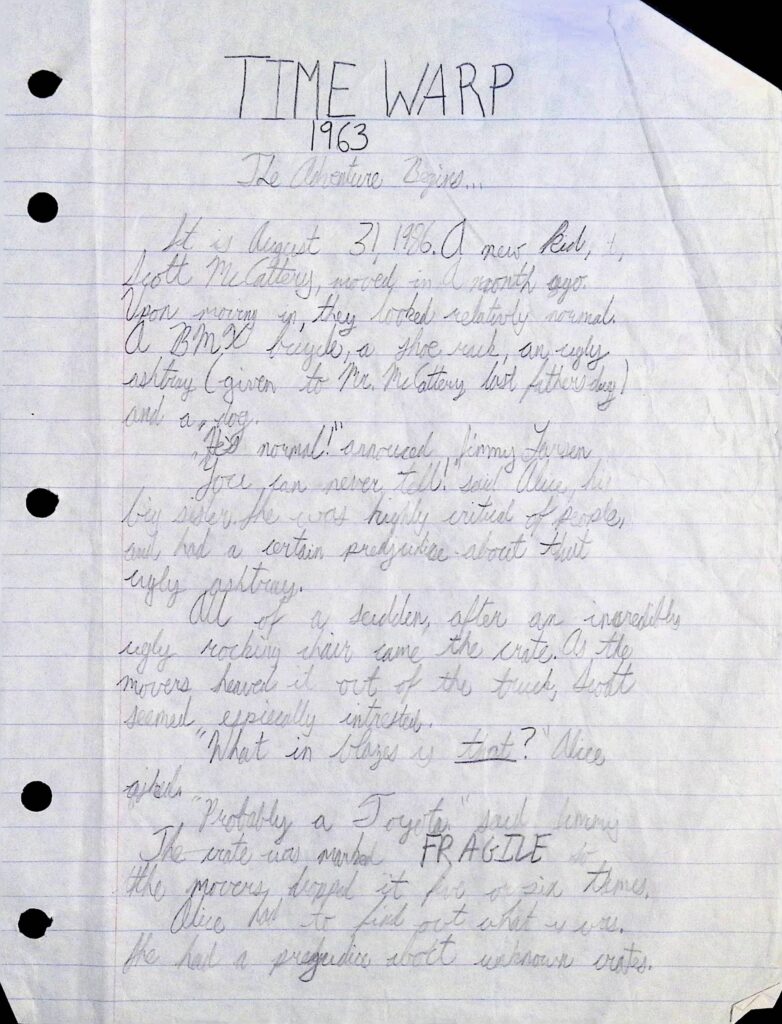

I write because I’m still mostly the deranged little boy who liked seeing adults bemused or freaked out by his stories (I wasn’t picky then and I’m still not). Any sign that I’ve reached a reader is a win.

A Scout is Brave has taken a long, long trek through the wilderness from first draft to this very moment, supported by many guides and fellow hikers for whom I’ll always be thankful. I’m grateful for all of you who critiqued its drafts, listened to it at campfires, encouraged me not to let it die, left reviews for it on websites, bought extra copies for your family members, and dressed as its characters for Hallowe’en.

Though I’m usually a rationalist, I’m not above a little superstition every now and then to hedge my bets. In my back pocket during the ceremony, I carried one of my old Boy Scout patches, along with another I found while going through the box of keepsakes: my mother’s patch from her career as a paramedic.

I thought they’d help curry favor with any allies pulling for me in the Great Beyond.

And yes, they absolutely worked.

Thanks again to all of you as well as the administrators of the awards, and congratulations to all of the nominees and winners!